The Vindication of Magnitude-Based Inference Will G

Hopkins, Alan M Batterham Sportscience 22, 19-29, 2018

(sportsci.org/2018/mbivind.htm) |

||||||

|

Authors' note. This article was published as a draft with post-publication peer

review. We invited readers to make supportive or critical comments using this template and submit as an attachment in an email to us. We published comments via this page

following any minor editing and interaction. This version incorporates points

raised in comments to date (24 August 2018). Future comments may be included

in a further update. The draft version with tracked changes resulting in this

version is available as a docx here. The

changes from the draft version are as follows… ·

From

the comments of Little (2018) and Lakens (2018), and our response (Batterham and Hopkins, 2018), MBI can be described as reference Bayesian inference with a

dispersed uniform prior. Two paragraphs starting here have been augmented. ·

The

comment of Wilkinson

(2018) supports our interpretation of errors

and error rates in MBI. We see no need

to modify our article in this respect. ·

When

the editor of Medicine and Science in

Sports and Exercise announced rejection of manuscripts using MBI, we

published a

comment (Hopkins and Batterham, 2018) recommending use of the Bayesian

description of MBI. We noted that the probability thresholds used by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are remarkably similar to those of

MBI, and we have updated this article accordingly here. We also critiqued an attack on MBI

by a journalist who used Sainani's erroneous error rates in a news item. We

noted two potentially damaging effects of the news item and of Sainani's

critique and include them here as an extra paragraph, followed by a paragraph

on avoiding underpowered studies. ·

The

comment of Buchheit

(2018) highlights the plight of a researcher

who understands and has opted for MBI, and for whom (in the absence of viable

alternatives) a return to p values is unthinkable. His comment represents an

endorsement of MBI by an experienced practitioner-researcher who suffered

under p values. No update of this article is required. ·

Some

researchers still need to understand how MBI works and how p values fail to

adequately represent uncertainty in effects. One of us (WGH) therefore put

together a slideshow and two videos, available via this comment (Hopkins, 2018). One of the slides is included below,

with an explanatory paragraph. ·

Soon

after publication of this version, someone raised the concern that MBI could

be viewed as promoting unethically underpowered studies. We have therefore

amended the paragraph

about small samples. Magnitude-based inference (MBI) is an approach to making a

decision about the true or population value of an effect statistic, taking

into account the uncertainty in the magnitude of the statistic provided by a

sample of the population. In response to concerns about error rates with the

decision process (Welsh

and Knight, 2015), we

recently showed that MBI is superior to the traditional approach to

inference, null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) (Hopkins and Batterham, 2016).

Specifically, the error rates are comparable and often lower than those of

NHST, the publishability rates with small samples are higher, and the potential

for publication bias is negligible. A statistician from Stanford University, Kristin Sainani, has

now attempted to refute our claims about the superiority of MBI to NHST (Sainani, 2018). We

acknowledge the effort expended in her detailed scrutiny and welcome the

opportunity to discuss the points raised in the spirit of furthering

understanding. Sainani argues that MBI should not be used, and that we should

instead "adopt a fully Bayesian analysis" or merely interpret the

standard confidence interval as a plausible range of effect magnitudes

consistent with the data and model. We have no objection to researchers using

either of these two approaches, if they so wish. Nevertheless, we have shown

before and show here again that MBI is a valid, robust approach that has

earned its place in the statistical toolbox. The title of Sainani's critique refers to "the

problem" with magnitude-based inference (MBI), but in the abstract she

claims that there are several problems with the Type-I and Type-II error

rates. In the article itself, she begins her synopsis of MBI with another

apparent problem: that the probabilistic statements in MBI about the

magnitude of the true effect are invalid. Throughout the critique are

numerous inconsistencies and mistakes. We solve here all her perceived

problems, highlight her inconsistencies and correct her mistakes. Should researchers make probabilistic assertions about the true

(population) value of effects? Absolutely, especially for clinically

important effects, where implementation of a possibly beneficial effect in a

clinical or other applied setting carries with it the risk of harm. We use

the term risk of harm to refer to

the probability that the true or population mean effect has the opposite of

the intended benefit, such as an impairment rather than an enhancement of a

measure of health or performance. It does not refer to risk of harm in a

given individual, which requires consideration of individual differences or

responses, nor does it refer to risk of harmful side effects, which requires

a different analysis. Magnitude-based inference is up-front with the chances

of benefit and the risk of harm for clinical effects, and the chances of

trivial and substantial magnitudes for non-clinical effects. This feature is

perhaps the greatest strength of MBI. Sainani states early on that "I

completely agree with and applaud" the approach of interpreting the

range of magnitudes of an effect represented by its upper and lower

confidence limit, when reaching a decision about a clinically important

effect. But, according to Sainani, "where Hopkins and Batterham's method

breaks down is when they go beyond simply making qualitative judgments like

this and advocate translating confidence intervals into probabilistic

statements, such as the effect of the supplement is 'very likely trivial' or

'likely beneficial.' This requires interpreting confidence intervals

incorrectly, as if they were Bayesian credible intervals." We have

addressed this concern previously (Hopkins and Batterham, 2016). The

usual confidence interval is congruent with a Bayesian credibility interval

with a minimally informative prior (Burton, 1994; Burton et al.,

1998; Spiegelhalter et al., 2004). As

such, it is an objective estimate of the likely range of the true value, and

the associated probabilistic statements of MBI are Bayesian posterior

probabilities with a minimally informative prior. The post-publication comments of

Little (2018) and

Lakens (2018) further

underscore this point. Unfortunately, full Bayesians disown us, because we prefer not

to turn belief into an informative subjective prior. Meanwhile, NHST-trained

statisticians disown us, because we do not test hypotheses. MBI is therefore

well placed to be a practical haven between a Bayesian rock and an NHST hard

place. (Others have attempted hybrids of Bayes and NHST, albeit with

different goals. See the technical notes.) From Bayesians we adapt valid

probabilistic statements about the true effect, based on the minimally

informative dispersed uniform prior. From frequentists (advocates of NHST) we

adapted straightforward computational methods and assumptions, and we

computed error rates for decisions based not on the null hypothesis but on

sufficiently low or high probabilities for the qualitative magnitude of the

true effect. The name magnitude-based

inference therefore seems justifiable, but in the Methods sections of

manuscripts, authors could or should note that it is a legitimate form of

Bayesian inference with the minimally informative dispersed uniform prior,

citing the present article. The appropriate reference for the decision

probabilities is the progressive statistics article in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (2009).

Whether the resulting error rates are acceptable is an issue we will address

shortly. There is a logical inconsistency in Sainani's "qualitative

judgment" of confidence intervals. In her view, it is not appropriate to

make a probabilistic assertion about the true magnitude of the effect, but it

is appropriate to interpret the magnitude of the lower and upper confidence

limits. The problem with this approach is that it all depends on the level of

the confidence interval, so she is in fact making a quantitative judgment. Indeed, such judgments are actually

nothing more or less than magnitude-based inference, the only difference

being the width of the confidence interval. Towards the end of her critique

she cites "an excellent reference on how to interpret confidence

intervals (Curran-Everett, 2009)."

Here is a quote from that article: "A confidence interval is a

range that we expect, with some level of confidence, to include the

true value of a population parameter… a confidence interval focuses our

attention on the scientific importance of some experimental result." In

the three examples he gives, Curran-Everett states that the true effect is

"probably" within the confidence interval or "could

range" from the lower to the upper confidence limit. Again, this

interpretation is quantitative, with probably

and could defined by the level of

confidence of the confidence interval. There is a further inconsistency with Sainani's applause for

qualitative judgments based on the confidence interval: the fact that her

concerns about error rates in MBI would apply to such judgments. Consider,

for example, a confidence interval that overlaps trivial and substantial

magnitudes. What is her qualitative judgment? The effect could be trivial or

substantial, of course. Where is the error in that pronouncement? If the true

effect is trivial, we say there is none, but she says there is an

unacceptable ill-defined Type-I error rate. The only way she can keep a

well-defined NHST Type-I error rate is to make a qualitative judgment only if the effect is significant. In

other words, if the confidence interval does not overlap the null, she can

say that the effect could be trivial or substantial, but if it does overlap

the null, however slightly, she cannot say that it could be trivial.

Presumably she will instead call the magnitude unclear. If that is the process of qualitative judgment she has

in mind, it is obviously unrealistic. Sainani is also inconsistent when she makes the following

statement: "Hopkins and Batterham's logic is that as long as you

acknowledge even a small chance (5-25%) that the effect might be trivial when

it is [truly trivial], then you haven't made a Type I error… But this seems

specious. Is concluding that an effect is 'likely' positive really an

error-free conclusion when the effect is in fact trivial?" Consider the

confidence-interval equivalent of Sainani's statement. A small chance that

the effect could be trivial corresponds to a confidence interval covering

mostly substantial values, with a slight overlap into trivial values, such

that the probability of a trivial true effect is only 6%, for example. Hence

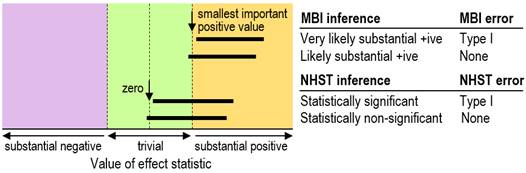

we say the effect could be trivial, so no Type-I error occurs (Figure 1).

Now consider what happens in NHST. If the 95% confidence

interval overlaps the null only slightly, with p=0.06, then a Type-I error

has not occurred (Figure 1). In other words, it's the same kind of decision

process as for MBI, except that in MBI the null is replaced with the smallest

important effect. The same argument could be mounted for Type-II errors:

Sainani does not specifically call our logic here specious, but she does show

later that our definitions "wildly underestimate" the traditional

Type-II error rates. We will not be held accountable for error rates based on

the null hypothesis. Sainani offers a novel solution to her perceived problem with

the definition of MBI Type-I error: allow for "degrees of error",

which inevitably makes higher Type-I error rates. But a similar inflation of

error rates would occur with NHST, if degrees of error were assigned to p

values that approach significance. We doubt if her solution would solve the

problems of the p value that are increasingly voiced in the literature; in

any case, we do not see the need for it with MBI. When an effect is possibly

trivial and possibly substantially positive, that is what the researcher has

found: it's on the way to being substantially positive. Furthermore, for

effects with true values that are close to the smallest important effect, the

outcome with even very large sample sizes will usually be possibly trivial and possibly substantial. Importantly, a

Bayesian analysis with any reasonable prior would reach this same conclusion,

because the prior is inconsequential with a sufficiently large sample size (Gelman et al., 2014). Now,

should such a finding be published? Of course, but we advise against making

inferences with the p value alone, because it will be <0.0001 and leave

the reader convinced that there is a substantial effect. It follows that such

outcomes with more modest sample sizes should also be published. By making a

clear possible outcome a publishable quantum, you also avoid substantial

publication bias, because researchers get more of their previously

underpowered studies into print with MBI. Adoption of MBI by the research

community would not result in a chaos of publication bias. On the contrary,

there would be negligible publication bias, and the farcical binary division

of results into statistically significant and non-significant at some

arbitrary bright-line p-value threshold would be consigned, along with the

null hypothesis, to the dustbin of failed paradigms. For researchers, reviewers and journal

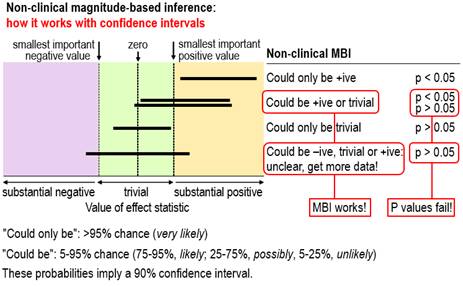

editors who are still undecided about using MBI in preference to p values,

see Figure 2, which is taken from the slideshow and second video, available

via this comment. The figure shows outcomes with small

samples where the interpretation of the magnitude of the confidence

limits–that is, MBI–provides a succinct and accurate description of the

uncertainty in the magnitude of the true effect, whereas p values fail. For

the two outcomes where the conclusion with non-clinical MBI is could be +ive or trivial, one is

significant and the researcher would conclude there is an effect, while the other is non-significant and the

researcher would conclude there is no

effect. Both conclusions based on

the p value are obviously wrong; the conclusion with MBI properly describes

the uncertainty. For the outcome where the MBI conclusion is unclear, the p

value again fails, because non-significance would be interpreted as no effect, which does not represent

the fact that the true value could be substantially negative, trivial or

substantially positive. We have given the conventional

NHST interpretations of significance and non-significance here; the

interpretations of what we called conservative

NHST, according to which the magnitude only of significant effects can be

interpreted (Hopkins and Batterham, 2016), fare

little better.

Turning now to the problem of error rates in MBI, we find some

agreement and some disagreement with Sainani about the definitions of error.

We consider that we made a breakthrough with our definitions, because they

focus on trivial and substantial magnitudes rather than the null. As we

stated in our Sports Medicine article (Hopkins and Batterham, 2016), a

valid head-to-head comparison of NHST and MBI requires definitions of Type-I

(false-positive) and Type-II (false-negative) error rates that can be applied

to both approaches. In the traditional definition of a Type-I error, a truly

null effect turns out to be statistically significant. Sample-size estimation

in NHST is all about getting significance for substantial effects, so we

argued that a Type-I error must also occur when any truly trivial effect is declared

significant. It was then a logical step to declare a Type-I error in any

system of inference when a truly trivial effect is declared substantial. Sainani appears to have

accepted this definition. However, she seems unable to accept our definition

of a Type-II error. In our definition, a Type-II error occurs when a true

substantial effect is declared either trivial or substantial of opposite

sign. It's a false-negative error, in the sense that you have failed to infer

the effect's true substantial magnitude and sign. This definition makes good

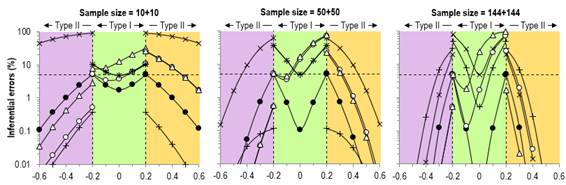

sense, especially when you consider a figure showing error rates on the Y

axis and true effects on the X axis (Figure 3). In her opening statement on definitions of error, Sainani states

that "Hopkins and Batterham are confused about what to call cases in

which there is a true non-trivial effect, but an inference is made in the

wrong direction (i.e., inferring that a beneficial effect is harmful or that

a harmful effect is beneficial). In the text, they switch between calling

these Type I and Type II errors." Yes, we may have caused confusion with

the following statement: "…implementation of a harmful effect

represents a more serious error than failure to implement a beneficial effect.

Although these two kinds of error are both false-negative type II errors,

they are analogous to the statistical type I and II errors of NHST, so they

are denoted as clinical type I and type II errors, respectively." They

are denoted as clinical Type-I and Type-II errors in the spreadsheet for

sample-size estimation at the Sportscience site, but they are correctly

identified as Type-II errors in our figure defining the errors, in the text

earlier in the article, and in the figures summarizing error rates. Sainani

goes on to state that "in their calculations, they treat them both as

Type II errors (Table 1a). But they can't both be Type II errors at the same

time." We do not understand this assertion, or her justification of it

involving one-tailed tests (but see the technical notes). She concludes with

"inferring that a beneficial effect is harmful is a Type II error,"

with which we agree, "whereas inferring that a harmful effect is

beneficial is a Type I error," with which we disagree. When a true

harmful effect is inferred not to be harmful, it is a Type-II error. Sainani

also notes that a true substantial effect inferred to be substantial of

opposite sign can be called a Type-III error, but we see no need for this

additional complication. That said, we do see the need to control the error

rate when truly harmful effects are inferred to be potentially beneficial.

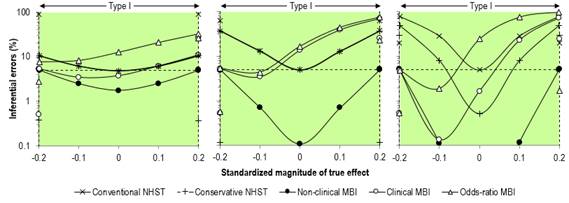

Our rebuttal of Sainani's assertions about error rates might not

satisfy fundamentalist adherents of NHST. Figure 3 shows our original figure

from the Sports Medicine article and an enlargement of the Type-I rates. We

did not misrepresent these rates in the text, but arguably we presented them

in a manner that favored MBI: "For null and positive trivial values, the

type I rates for clinical MBI exceeded those for NHST for a sample size of

50+50 (~15–70 % versus ~5–40 %), while for the largest sample size, the type

I rates for clinical MBI (~2–75 %) were intermediate between those of

conservative NHST (~0.5–50 %) and conventional NHST (5–80 %)." These

error rates are consistent with those presented by Sainani, but the changes

of scale for the different true-effect magnitudes in her figure gives an

unfavorable impression of the MBI rates. We gave an honest account of the higher Type-I error rates with

odds-ratio MBI, which Sainani did not address. Our justification for keeping

this version of MBI in the statistical toolbox along with clinical MBI seems

reasonable. From the Sports Medicine article: "The Type-I rates for

clinical MBI were substantially higher than those for NHST for null and

positive true values with a sample size of 50+50. The probabilistic

inferences for the majority of these errors were only possibly beneficial, so

a clinician would make the decision to use a treatment based on the effect,

knowing that there was not a high probability of benefit. Type-I error rates

for odds-ratio MBI were the largest of all the inferential methods for null

and positive trivial effects, but for the most part these rates were due to

outcomes where the chance of benefit was rated unlikely or very unlikely, but

the risk of harm was so much lower that the odds ratio was >66. Inspection

of the confidence intervals for such effects would leave the clinician with

little expectation of benefit if the effect were implemented, so the high

Type-I error rates should not be regarded as a failing of this

approach." In her discussion, Sainani asserts: "Whereas standard

hypothesis testing has predictable Type I error rates, MBI has Type I error

rates that vary greatly depending on the sample size and choice of thresholds

for harm/benefit. This is problematic because unless researchers calculate

and report the Type I error for every application, this will always be hidden

to readers." But the "well-defined" Type-I rate for NHST is

only for the null; for trivial true effects it also varies widely with sample

size and choice of magnitude thresholds, and this variation is also hidden

from readers. The fact that the Type-I error rate for MBI peaks at the

optimum sample size (the minimum sample size for practically all outcomes to

be clear) is no cause for concern, because sample-size estimation in MBI is

based on controlling the Type-II rates. She goes on with this particularly

galling assertion: "Furthermore, the dependence on the thresholds for

harm/benefit makes it easy to game the system. A researcher could tweak these

values until they get an inference they like." This is a fatuous charge

to level against MBI. Any system of inference is open to abuse, if

researchers are so minded. A researcher who assesses the importance of

a statistically significant or non-significant outcome can choose the value

of the smallest important effect at that stage to suit the outcome obtained

with the sample. Researchers also game the NHST system by providing a justification

for sample size based on moderate effects. Sainani presumably has the same

concerns about full (subjective) Bayesians gaming not only the smallest

important effect but also the prior to get the most pleasing or publishable

outcome. Sainani's only remaining substantial concern about our

definition of error rates is not so easily dismissed. MBI provides a new

category of inferential outcome: unclear,

which is synonymous with unacceptably

uncertain, inadequately precise,

or perhaps most importantly, indecisive.

In our definition of Type-I and Type-II errors, you can't make an error until

you make a decision about the magnitude. The spreadsheets at the Sportscience

site (sportsci.org) state: "unclear; get more data." Hence we do

not include unclear as a Type-II

error when the true effect is substantial, or indeed as a Type-I error when

the true effect is trivial, a point that Sainani did not make. We applied

this definition even-handedly to what we call conservative NHST, where

researchers do not make a decision about an effect unless it is statistically

significant. A major outcome of our study of the various kinds of inference

is that the rates of decisive (and therefore publishable) effects for small

sample sizes with MBI are surpassed only by those with conventional NHST,

which is 100% decisive but pays for it with huge Type-II error rates. The

other major outcome is the trivial publication bias with MBI, whereas the

bias is substantial with NHST in both its forms. If the error rates with MBI

are as high as Sainani asserts, they obviously do not have implications for

publication bias. We have no hesitation about keeping indecisive outcomes out

of the rates of making wrong decisions, but if writing off MBI is on your

agenda, you will continue to assert that unclear outcomes are inferential

errors. Sainani concludes her critique with the following solution to fix what she regards as the MBI Type-I error problem: "…a one-sided null hypothesis test for benefit–interpreted alongside the corresponding confidence interval–would achieve most of the objectives of clinical MBI while properly controlling Type I error." We disagree. First, we do not wish to conduct "tests" of any kind; we embrace uncertainty and prefer estimation to "testimation", to borrow from Ziliak and McCloskey (2008). Secondly, the p value from her proposed one-sided test against the non-zero null given by the minimum clinically important difference is precisely equivalent to 1 minus the probability of benefit from MBI. If the one-sided test is conducted at a conventional 5% alpha level, the implication is that Sainani requires >95% chance of benefit to declare a treatment effective–equivalent to our very likely threshold. Elsewhere in her article, however, she suggests that "…clinical MBI should revert to a one-sided null hypothesis test with a significance level of 0.005." This test implies a requirement for a minimum probability of benefit of 0.995–equivalent to our most likely or almost certainly threshold. We regard both of these thresholds–and one-sided tests at 2.5% alpha favored in regulatory settings–as too conservative, particularly as clinicians and practitioners we have worked with over many years tell us that a 75% chance of benefit–or odds of 3:1 in favor of an intervention–is a cognitive tipping point for decision-making in the absence of substantial risk of harm. We also acknowledge that caution is warranted in making definitive inferences or decisions on the basis of a single study, but this is perhaps less of a problem, if the single study is a large definitive trial with a resulting precise estimate of treatment effect (Glasziou et al., 2010). Before we leave the issue of error rates, it is important to

note that the theoretical basis of NHST is now held to be untrustworthy by

some highly cited establishment statisticians. Consider, for example, the

following comments of two contributors to the American Statistical

Association's policy statement on p values (Wasserstein and Lazar, 2016; see the supplement):

"we should advise today’s students of statistics that they should avoid

statistical significance testing (Ken Rothman)" and "hypothesis

testing as a concept is perhaps the root cause of the problem (Roderick

Little)." If they are right, it follows that the traditional definitions

of Type-I and Type-II errors, both of which are based on the null hypothesis,

are themselves unrealistic and untrustworthy. Our definitions deserve more

recognition as a possible way forward. In her criticisms of the theory of MBI, Sainani claims that the

three references we cited in our Sports Medicine

article to support the sound theoretical

basis of MBI "do not provide such

evidence." We will now show that her claim is misleading

or incorrect for all three references. The first reference is Gurrin et al. (2000), from

which she quotes correctly: "Although the use of a uniform prior

probability distribution provides a neat introduction to the Bayesian

process, there are a number of reasons why the uniform prior distribution

does not provide the foundation on which to base a bold new theory of

statistical analysis!" However, she neglects to point out that later in

the same article Gurrin et al. make this statement: "One of the problems

with Bayesian analysis is that it is often a non-trivial problem to combine

the prior information and the current data to produce the posterior

distribution… The congruence between conventional confidence intervals and

Bayesian credible intervals generated using a uniform prior distribution

does, however, provide a simple way to obtain inferences in Bayesian form

which can be implemented using standard software based on the results and

output of a conventional statistical analysis… Our approach [effectively MBI]

is straightforward to implement, offers the potential to describe the results

of conventional analyses in a manner that is more easily understood, and leads naturally to rational decisions

[our italics]." Her claim about this reference is therefore misleading

and by omission, wrong. The second reference supporting MBI is Shakespeare et al. (2001).

Sainani states that this article "just provides general information on

confidence intervals, and does not address anything directly related to

MBI." On this point she is also wrong. The method presented by

Shakespeare et al. to derive what they refer to as "confidence

levels" uses precisely the same methods as MBI to derive the probability

of benefit beyond a threshold for the minimum clinically important difference.

For example, the authors present the following re-analysis of a previously

published study using their method: "The study found a survival benefit

of 28% favoring immediate nodal dissection (hazard ratio 0·72, 95% CI

0·49–1·04). There is a… 94% level of confidence [i.e., chance of benefit]

that the survival benefit is clinically relevant (improvement in survival of

3% or more). The information contained

in confidence levels is clearly far more useful than CIs alone to clinicians

in applying results to daily practice [our italics]." This method is

very obviously MBI in all but name. Shakespeare et al. also calculated the

risk of harm, but it was the risk of harmful side effects, not the risk of the opposite of a beneficial

outcome. The third reference that she claims does not provide evidence

supporting MBI is our letter to the editor (Batterham and Hopkins, 2015) in

response to the article by Welsh and Knight (2015). By her

account, this reference "is a short letter in which they point to

empirical evidence from a simulation that I believe is a preliminary version

of the simulations reported in Sports Science [sic]." But the issue here

is the theoretical basis of MBI, which indeed we had argued succinctly in the

letter. Hence this claim also is wrong. Finally, the overarching negative tone of Sainani's critique

deserves attention. We counted three occasions in the article where she gives

any credit to our achievement with MBI, but each is immediately followed by

an assertion that we were misguided or mistaken. She is the one who is

misguided or mistaken. It is deeply disappointing and discouraging when

someone in her position of influence fails to notice or acknowledge the

following novel contributions that

we have made to the theory and practice of inference: the definitions of

inferential error that go beyond the null (nil) hypothesis and statistical significance;

sample-size estimation based on controlling these errors, especially the risk

of declaring a harmful effect potentially implementable; the higher

publishability rates and negligible publication bias with MBI compared with

NHST; quantitative ranges for qualitative measures of probability; smallest

and other magnitude thresholds for the full range of effect statistics in the

sports-medicine and exercise-science disciplines; procedures for estimating

and assessing the magnitude of the standard deviation representing individual

responses with continuous outcomes and of the moderators explaining them; the

need for a distinction between clinical and non-clinical inference; the

concept of clear effects with the

two kinds of inference, and the associated decision rules based on adequate

precision or acceptable uncertainty; and easily the most valuable of all, the

notion of accounting for the risk of harm–the probability that the true

effect represents impairment rather than enhancement of health or performance–with

clinically important effects. There is still room for debate that

could result in improvements in MBI. The most obvious debatable feature are

the rules we have devised for deciding when effects are clear in clinical and

non-clinical settings–in other words, the rules for acceptable uncertainty in

the two settings. These rules in turn depend on the threshold probabilities

that define the terms most unlikely,

very unlikely, unlikely, possible, likely, very likely and most likely, because it is only with

these or similar qualitative terms that researchers, clinicians and

practitioners can make informed decisions as stakeholders. The decision must

not be left solely with the statisticians. Some will argue that these

thresholds are as arbitrary as the p value of 0.05 defining significance. Our

rejoinder is that our thresholds are for real-world probabilities based on

experience with clinicians and practitioners. They are also similar to, and a

little more conservative than, those used by the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change (Mastrandrea et al., 2010),

another group of scientists who are concerned about communicating decisions

based on plain-language probabilities of outcomes. Furthermore, our

simulations showed that they provide realistic publication rates and

negligible publication bias for small-sample research. Anyone wishing to

define clear more conservatively

will inevitably reduce publication rates and increase publication bias. We have demonstrated that the error rates in MBI are acceptable overall. However, those wishing to use MBI, but who remain concerned with error rates, could present an additional statistic with excellent error control, the second-generation p-value (SGPV) (Blume et al., 2018). Briefly, this statistic is based on an interval null hypothesis equivalent to the trivial region in MBI. The SGPV is not a probability; rather it is the proportion of hypotheses supported by the data and model that are trivial. If the SGPV=0, then the data support only clinically meaningful hypotheses. If the SGPV=1, then the data support only trivial hypotheses. Values between 0 and 1 reflect the degree of support for clinically meaningful or trivial hypotheses, with a SGPV of 0.5 indicating that the data are strictly inconclusive. If the attack on MBI results in

journal editors banning the use of MBI in submitted manuscripts, and if the

editors do not accept MBI as reference

Bayesian analysis with a dispersed uniform prior, what is the

alternative? We have shown that simple presentation of the confidence

interval is effectively MBI, and that hypothesis tests against the smallest

important effect are far too conservative. Researchers may therefore have to

make the choice between Bayesian analysis with informative priors and a return to p values. We have argued in a comment

(Hopkins and Batterham, 2018) that

full Bayesian analyses are generally unrealistic and challenging for most

researchers, which leaves p values as Hobson's choice for researchers and a

stop-gap choice for reviewers and editors. In the same comment, we pointed

out the following two unfortunate consequences. First, many small-scale

studies with clear outcomes in MBI will no longer be publishable, because the

outcomes will not be significant. These effects, which do not suffer from

substantial bias, will no longer contribute to meta-analyses, where they

would have helped push the overall sample size up to something that gives

definitive outcomes. Meta-analyses based on a large number of small studies

rather than a few large studies also give better estimates of the modifying

effects of study and subject characteristics and thereby better

generalizability to more settings. Secondly, it will be harder for research

students to get publications, because they will need larger sample sizes to

get significance, often impractically large when the subjects are competitive

athletes. Their careers will therefore suffer needlessly. The lack of substantial bias with

MBI should not be used as an excuse for performing underpowered studies. In

the simulations of controlled trials where the MBI-optimal sample size was 50

in each group, a sample size of 10 in each group resulted in ~55-65% unclear

non-clinical effects and ~20-65% unclear clinical effects over the range of

true trivial effects (Hopkins and Batterham, 2016). It is

unethical to undertake research when the expectation of a decisive outcome

for trivial effects is determined by a coin toss, but when an optimal sample

size for trivial effects is not possible, should the research should still be

performed? Yes, if there is a genuine expectation that the effect will have

sufficient magnitude to be clear, or if another cohort of participants can be

recruited eventually to make the sample size adequate (although the bias with

a group-sequential design in MBI has yet to be investigated). The smaller

sample sizes for publishability with MBI reduce the risk of unethically underpowered

studies compared with NHST. In conclusion, MBI represents a trustworthy mechanism for

representing the uncertainty in effects with well-defined qualitative

categories of probability. It beggars belief that any journal reviewer or

editor could take exception to publication of an effect as being harmful, trivial, beneficial, substantial

increase, or substantial decrease

prefaced by possibly, likely, very

likely, or most likely. Such

outcomes, along with unclear,

should be welcomed as a sunny spring following a long dark winter of p-value

discontent. Instead, MBI has now experienced two one-sided negative

critiques. The current critique turns largely on the assertion that possibly beneficial outcomes in

clinical MBI and unlikely trivial

and possibly trivial outcomes in

non-clinical MBI have unacceptably high Type-I error rates. We have shown

that the error rates are generally lower than those of NHST, and where any

are high, they are comparable with those of NHST. By communicating the

uncertainty in the magnitude of effects in plain language, by increasing the

rates of publishability, and by eliminating the potential for publication

bias, MBI has provided a valuable service to the research community. A return

to hypothesis testing, p values and statistical significance is unthinkable.

MBI should be used. Acknowledgments: Thanks to Steve Marshall, Ken Quarrie and Fabio Serpiello, who provided useful feedback on drafts. Thanks also to those who responded with the published comments, and to colleagues at Victoria University (Fabio Serpiello, Steph Blair, Luca Oppici, and Craig Pickett), who provided feedback on the slideshow/videos, and to Ken Quarrie, who provided the Sainani-style error graphics therein. Technical notes

Throughout

this article, null means nil or zero, rather than Fisher's generic conception of the hypothesis

to be nullified (Cohen, 1994). We

make this point, because some have argued that, instead of MBI or full

Bayesian inference, one could perform a hypothesis test against the minimum

important difference, rather than against the nil hypothesis, and present a p

value for that test (e.g., Greenland et

al., 2016).

Sainani may have had this in mind when she wrote: "In addition, a

one-sided null hypothesis test for benefit–interpreted alongside the

corresponding confidence interval–would achieve most of the objectives of

clinical MBI while properly controlling Type I error." Here, by null she presumably means the hypothesis to be nullified: the

smallest important beneficial effect. Some

full Bayesians have previously taken exception to the non-informative or

"flat" prior of MBI, by invoking two arguments. First, representing

such a prior mathematically is an intractable problem (Barker and Schofield, 2008). We

delighted in parodying this argument by calling the flat prior an imaginary

Bayesian monster (Hopkins and

Batterham, 2010): the

argument is easily dismissed simply by making the prior minimally

informative, which makes the prior tractable but makes no substantial

difference to the posterior. The second argument is that a uniform flat or

minimally informative prior must become non-uniform, if the dependent

variable is transformed, for example using logarithms or any of the

transformations in generalized linear modeling (e.g., Gurrin et al., 2000). Again,

this argument is easily dismissed: the flat or minimally informative prior is

applied to the transformation of the dependent variable in a model that makes

least non-uniformity of the effect and error compared with any other

transformations (including non-transformation) and models. What happens to

the prior with these other transformations and models is irrelevant. Interestingly,

if we were full Bayesians, we might not be expected to concern ourselves with

error control, as some full Bayesians distinguish "beliefs" from

estimates of "true" values; for them, frequentist notions such as

Type-I errors do not exist (Ventz and Trippa, 2015). A full

Bayesian–with the caveat that more than 30 years ago there were already

46,656 kinds (Good, 1982)–might

say, for example, that "75% of the credible values exceed the minimum

clinically important threshold for benefit”, whereas the MBI exponent would

claim that "the probability that the true value of the treatment exceeds

the threshold for benefit is 75%; that is, the treatment is likely

beneficial." In MBI, adopting a least-informative prior and making

decisions based on a posterior distribution equivalent to the likelihood

arguably requires us to give due consideration to error control, which we

have done. The general notion of Bayesian inference with a model chosen to

yield inferences with good frequency properties has been described as

"Calibrated Bayes" (Little, 2011; Little, 2006). Other

attempts at reconciling Bayesian and frequentist paradigms include

"Constrained Optimal Bayesian" designs (Ventz and Trippa, 2015). Meanwhile, to make probabilistic statements, Sainani

recommends we adopt a full Bayesian analysis, in which there is no apparent

requirement for error control, while lambasting MBI for having higher error

rates in some scenarios. Her position once again is inconsistent. References

Cohen J (1994). The earth is round (p < .05). American Psychologist 49, 997-1003 Mastrandrea MD, Field CB, Stocker TF, Edenhofer O, Ebi KL, Frame DJ, Held H, Kriegler E, Mach KJ, Matschoss PR, Plattner G-K, Yohe GW, Zwiers FW (2010). Guidance Note for Lead Authors of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report on Consistent Treatment of Uncertainties. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/supporting-material/uncertainty-guidance-note.pdf Draft 2 published

14 May 2018. |