|

Wilbur Olin Atwater (1844-1907)

Atwater received his PhD from Yale in 1869 for studies on the

chemical composition of corn. Studying in Berlin and Leipzig, he became

familiar with the eminent German chemists and physiologists Voit, Rubner,

and Zuntz. As Professor of Chemistry at Wesleyan College in Connecticut,

USA, he studied the effects of fertilizers in farming and established

the first agricultural experimental station in the United States at

Wesleyan in 1875 (which in 1877 became part of the famous Sheffield

Scientific School at Yale University). From 1879 to 1882 Atwater determined

the chemical composition and nutritive values of fish and animal tissues.

Returning to Germany in 1882-83, Atwater studied the metabolism of mammals

in Voit's laboratory. Atwater received his PhD from Yale in 1869 for studies on the

chemical composition of corn. Studying in Berlin and Leipzig, he became

familiar with the eminent German chemists and physiologists Voit, Rubner,

and Zuntz. As Professor of Chemistry at Wesleyan College in Connecticut,

USA, he studied the effects of fertilizers in farming and established

the first agricultural experimental station in the United States at

Wesleyan in 1875 (which in 1877 became part of the famous Sheffield

Scientific School at Yale University). From 1879 to 1882 Atwater determined

the chemical composition and nutritive values of fish and animal tissues.

Returning to Germany in 1882-83, Atwater studied the metabolism of mammals

in Voit's laboratory.

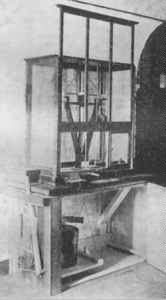

| Cycle ergometer used by Atwater and his colleague

Benedict in their studies

on exercise metabolism.

|

|

|

|

The sensitive balance scales Atwater used in his metabolic

studies.

|

|

|

Atwater's familiarity with German techniques for measuring respiration

and metabolism helped him to conduct studies on food analysis, dietary

evaluations, energy requirements for work, digestibility of foods, and

economics of food production. He helped to persuade the United States

Government to fund studies of human nutrition. Atwater directed various

studies at agricultural experiment stations throughout the country that

resulted in the 1896 publication of 2600 chemical analyses of American

foodstuffs. An additional 4000 analyses were completed in 1899, including

another 1000 analyses done under Atwater's supervision. The 1906 re-issue

of the original report included the maximum, minimum, and average values

for water, protein, fat, total carbohydrates, ash, and a food's "fuel

value" calculated using Rubner's methods. Most commercial diet analysis

programs currently incorporate Atwater's databases of food composition

values.

Atwater compared US food evaluations with those from Europe. Although

Voit and other agricultural chemists advocated a minimum protein intake

of over 100 grams per day, Atwater felt this amount to be excessive.

He recommended controlled dietary studies to determine how nutrient

intake affected metabolism and muscular effort. After reviewing his

dietary studies, Atwater worried that the population consumed too much

food, particularly fats and sweets, and did not exercise enough:

It is a fair question whether the results of these things have induced

among us in a large class of well-to-do people, with little muscular activity,

a habit of excessive eating and may be responsible for great damage to

health, to say nothing of the purse (Maynard,1962, citing Atwater.) .

|

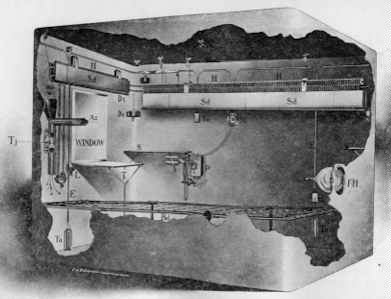

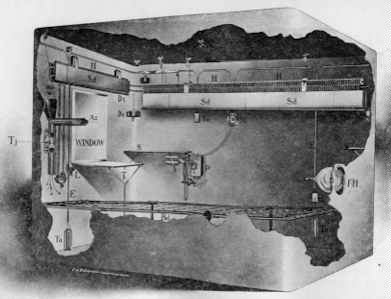

Inside the Atwater-Benedict human calorimeter.

|

|

|

The metabolic studies Atwater began just before the turn of the century

contributed most to the emerging science of human nutrition and exercise.

Over a 12-year period he and E. B. Rosa (Professor of Physics at Wesleyan,

and later chief physicist of the National Bureau of Standards) perfected

the most accurate respiration calorimeter for studies of human metabolism.

Accounting for almost 100 percent of the heat produced and substrates

metabolized, this system allowed them to quantify the dynamics of energy

metabolism, directly measure the balance between food (energy) intake

and energy output, and evaluate the effects of diet and muscular activity

on metabolism. The classic papers of Atwater and Rosa (1899), Atwater

and Benedict (1905.), and Benedict and Carpenter (1910), with their

meticulous technical detail and experimental procedures, should be studied

by all who are interested in exercise nutrition.

|

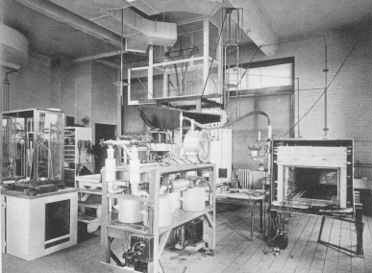

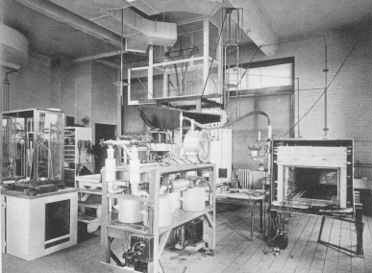

Atwater's scientific lab.

|

|

|

Before Atwater died in 1907, he had completed more than 500 energy-balance

experiments. Maynard (1962) believes that Atwater's most valuable contributions

concerned human energy balance. They confirmed that the law of conservation

of energy governed transformation of matter in both the human body and

inanimate world. Atwater's comments penned in 1895 sound contemporary:

Food may be defined as material which, when taken into the body,

serves to either form tissue or yield energy, or both. This definition

includes all the ordinary food materials, since they both build tissue

and yield energy. It includes sugar and starch, because they yield energy

and form fatty tissue. It includes alcohol, because the latter is burned

to yield energy, though it does not build tissue. It excludes creatin,

creatininin, and other so-called nitrogeneous extractives of meat, and

likewise thein or caffein of tea and coffee, because they neither build

tissue nor yield energy, although they may, at times, be useful aids to

nutrition (Atwater, 1905).

|

| For other history makers in exercise nutrition,

refer to McArdle, W.D., Katch, F.I., and Katch, V.L..

Sports and Exercise Nutrition. Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore,

1999. See preview (from mid-March). |

|

|

References

Atwater, W. O. (1895). Methods and Results of Investigations on the

Chemistry and Economy of Food. Bulletin 21, U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Office of Experiment Stations, Government Printing Office, Washington,

D.C.

Atwater, W. O., and Rosa, E. B. (1899). Description of a New Respiration

Calorimeter and Experiments on the Conservation of Energy in the Human

Body, Bulletin 63, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of Experiment

Stations, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Atwater, W. O., and Benedict, F. G. (1905). A Respiration Calorimeter

with Appliances for the Direct Determination of Oxygen, Carnegie Institute

of Washington, Washington, D.C.

Benedict, F. G., and Carpenter, T. M. (1910). Respiration Calorimeters

for Studying the Respiratory Exchange and Energy Transformations of

Man, Bulletin 123, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of Experiment

Stations, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Maynard, L. A. (1962). Wilbur O. Atwater-a biographical sketch. Journal

of Nutrition, 78, 3.

©1999

Edited and webmastered by Will Hopkins · Last updated 22 Feb 1999 |

Atwater received his PhD from Yale in 1869 for studies on the

chemical composition of corn. Studying in Berlin and Leipzig, he became

familiar with the eminent German chemists and physiologists Voit, Rubner,

and Zuntz. As Professor of Chemistry at Wesleyan College in Connecticut,

USA, he studied the effects of fertilizers in farming and established

the first agricultural experimental station in the United States at

Wesleyan in 1875 (which in 1877 became part of the famous Sheffield

Scientific School at Yale University). From 1879 to 1882 Atwater determined

the chemical composition and nutritive values of fish and animal tissues.

Returning to Germany in 1882-83, Atwater studied the metabolism of mammals

in Voit's laboratory.

Atwater received his PhD from Yale in 1869 for studies on the

chemical composition of corn. Studying in Berlin and Leipzig, he became

familiar with the eminent German chemists and physiologists Voit, Rubner,

and Zuntz. As Professor of Chemistry at Wesleyan College in Connecticut,

USA, he studied the effects of fertilizers in farming and established

the first agricultural experimental station in the United States at

Wesleyan in 1875 (which in 1877 became part of the famous Sheffield

Scientific School at Yale University). From 1879 to 1882 Atwater determined

the chemical composition and nutritive values of fish and animal tissues.

Returning to Germany in 1882-83, Atwater studied the metabolism of mammals

in Voit's laboratory.