|

Claude Bernard (1813-1878)

Bernard, generally acclaimed as the greatest physiologist of

all time, succeeded François Magendie as Professor of Medicine at the Collège

de France. Bernard interned in medicine and surgery before serving as

laboratory assistant (préparateur) to Magendie in 1839.

Three years later, he followed Magendie to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital

in Paris. For the next 35 years, Bernard discovered fundamental properties

about physiology. He participated in the explosion of scientific knowledge

in the mid century. Following Darwin's The Origin of Species

(1859), Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) refuted spontaneous generation between

1860 and 1865 and stimulated the growth of microbiology. In 1865, Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884) promulgated the laws of heredity. Artists too experimented

with technique (Corbet, Courbet, Degas, Daumier, Manet, Millet, Monet,

Renoir, and Rodin). Philosophers (de Tocqueville, Comte, Bergson, Proudhon)

and writers (Balzac, Baudelaire, Dumas, Hugo, Flaubert, Maupassant,

Stendhal) boldly explored new frontiers. Radical individualism that

fostered science and art also encouraged social turmoil: coups, two

revolutions (1848, 1870), and two wars against Austria and Prussia.

Reflecting on this unrest, Marx and Engels drafted the Communist

Manifesto in Paris 1848. Bernard, generally acclaimed as the greatest physiologist of

all time, succeeded François Magendie as Professor of Medicine at the Collège

de France. Bernard interned in medicine and surgery before serving as

laboratory assistant (préparateur) to Magendie in 1839.

Three years later, he followed Magendie to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital

in Paris. For the next 35 years, Bernard discovered fundamental properties

about physiology. He participated in the explosion of scientific knowledge

in the mid century. Following Darwin's The Origin of Species

(1859), Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) refuted spontaneous generation between

1860 and 1865 and stimulated the growth of microbiology. In 1865, Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884) promulgated the laws of heredity. Artists too experimented

with technique (Corbet, Courbet, Degas, Daumier, Manet, Millet, Monet,

Renoir, and Rodin). Philosophers (de Tocqueville, Comte, Bergson, Proudhon)

and writers (Balzac, Baudelaire, Dumas, Hugo, Flaubert, Maupassant,

Stendhal) boldly explored new frontiers. Radical individualism that

fostered science and art also encouraged social turmoil: coups, two

revolutions (1848, 1870), and two wars against Austria and Prussia.

Reflecting on this unrest, Marx and Engels drafted the Communist

Manifesto in Paris 1848.

Bernard remained oblivious to all except his "physico-chemical science."

Mayer (1951) writes about Bernard's approach to science:

Bernard combined with a capacity for hard and prolonged work in the

laboratory his appreciation of the importance of leisure spent in

quiet meditation. His adherence to exact truth was absolute, and he

was always ready to recognize the limitations or the error of what

had seemed like a promising idea until tested in the laboratory. His

technical skill was superb, both as an experimental surgeon and as

a biochemist. Yet essential as these characteristics were, they are

not sufficient to explain his unequaled series of fertile discoveries.

Bernard, first of all, believed strongly in the necessity of always

having a working hypothesis, derived from perusal of the literature

and observation of natural phenomena, before starting on the experiment

proper. He used to say: "He who does not know what he is looking for

will not lay hold of what he has found when he gets it."

But imagination is not equivalent to genius unless it is joined to

what was perhaps Bernard's outstanding characteristic, the ability

to devise the single, definitive crucial experiment which will test

a far-reaching hypothesis. Bernard, like a great general who maps

and executes a campaign by striking at the vital points of the enemy

hosts, and takes only those positions which have to be taken to bring

decisive victory, never wasted any time on experiments which were

not essential to his progress. And, of course, his skill allowed him

to perform these experiments in a minimum of time and with a maximum

of precision.

Bernard had an extraordinary capacity for extracting from his results

the most general and far-reaching conclusions that could be solidly

supported by them; hence, his role as a progenitor in so many branches

of the biological sciences.

| Claude Bernard surrounded by

his pupils during one of his many experiments. The original

is in the Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Paris.

Drawing by L'Hermitte. |

|

|

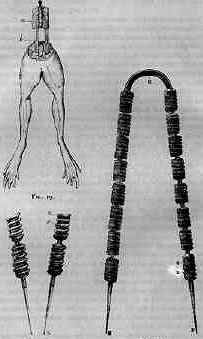

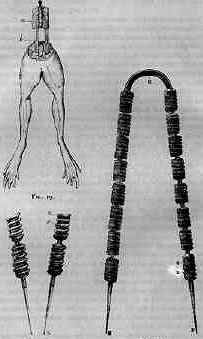

| Surgical instruments

used by Bernard in his studies of electrical stimulation of

tissues and the effects of the drug curare, a topic of extreme

interest to him since his early school days. |

|

|

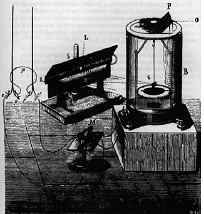

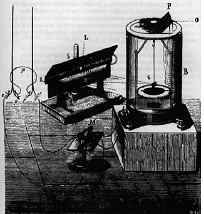

| Scientific apparatus used by

Bernard in his classic experiments of blood flow in the brain

|

|

|

Bernard indicated his single-minded devotion to research by producing

an M.D. thesis (1843) on gastric juice and its role in nutrition (Du

sac gastrique et de son rôle dans la nutrition). Ten years

later, he received the Doctorate in Natural Sciences for his study entitled

Recherches sur une nouvelle fonction du foie, consideré comme

organe producteur de matière sucrée chez l'homme et les

animaux (Research on a new function of the liver as a producer of

sugar in man and animals). Prior to his seminal research, scientists

assumed that only plants could synthesize sugar, and sugar within animals

must be derived from ingested plant matter. Bernard disproved this notion

by documenting the presence of sugar in the hepatic vein of a dog whose

diet lacked carbohydrate.

Bernard's experiments changed medicine (Fruton, 1979):

- The discovery of the role of the pancreatic secretion in the digestion

of fats (1848).

- The discovery of a new function of the liver--the "internal secretion"

of glucose into the blood (1848).

- The induction of diabetes by puncture of the floor of the fourth

ventricle (1849).

- The discovery of the elevation of local skin temperature upon section

of the cervical sympathetic nerve (1851).

- The production of sugar by washed excised liver (1855) and the isolation

of glycogen (1857).

- The demonstration that curare specifically blocks motor nerve endings

(1856).

- The demonstration that carbon monoxide blocks the respiration of

erythrocytes (1857).

|

|

| Claude Bernard after

winning a prestigIous award for his many scientific accomplishments.

|

Bernard's work also influenced other sciences. His discoveries in chemical

physiology spawned physiological chemistry and biochemistry, which in

turn created molecular biology. His contributions to regulatory physiology

helped the next generation understand how metabolism and nutrition affected

exercise.

Despite the importance of Bernard's discoveries, the French government

barely supported scientific research. Germany, Russia, and England provided

laboratories in universities and hospitals. Bernard's predecessors,

Magendie and Bert, worked in small rooms, poorly lit and inadequately

ventilated (Guerlac, 1977). Bernard spoke out against his government's

neglect of science. Still, he continued to experiment.

Bernard's influential Introduction à l'étude de la

médecine expérimentale (The Introduction to the Study

of Experimental Medicine, 1865)4 illustrates the self control that enabled

him to succeed despite external perturbations. It requires researchers

to vigorously observe, hypothesize, and test their hypothesis. In the

last third of the book, Bernard shares his strategies for verifying

results. His disciplined approach remains valid, and should be required

reading for all scientists, regardless of the field.

Bernard's life inspired appreciative works by the Cambridge physiologist

Sir Michael Foster (1899) and historian Grmek (1971). A few days after

his death, Bernard's friend and colleague Paul Bert wrote the following

poignant eulogy (see preface of Bernard, 1927):

Nothing in his pure and harmonious life was turned aside from its

chief aim. Enamored of literature, art and philosophy, Claude Bernard

as a physiologist lost nothing by these noble passions; on the contrary,

they all helped in developing the science with which he identified

himself, and of which he is the highest and most complete embodiment.

He as a physiologist such as no man had been before him. "Claude Bernard,"

said a foreign scientist, "is not merely a physiologist, he is physiology."

His very death seems to mark a new era in science. For the first

time in our country, a man of science will receive those public honors

hitherto reserved for political and military celebrities.... And one

phrase... sums up all that we have said: "The light, which has just

been extinguished, cannot be replaced."

References

Bernard, C. (1927).The introduction to the study of experimental

medicine (translated by H. C. Greene). Henry Schuman, New York.

Foster, M. (1899). Claude Bernard. Longmans Green, New York.

Fruton, J. S. (1979). Claude Bernard the scientist. In E. D. Robin

(Ed.) Claude Bernard and the internal environment. A memorial symposium.

Marcel Dekker, New York.

Grmek, M. D. (1971). Claude Bernard. In Dictionary of scientific

biography. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

Guerlac, H. G. (1977). Essays and papers in the history of modern

science. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Mayer, J. (1951). Claude Bernard. Journal of Nutrition, 45,

3.

© Frank I. Katch,

William D. McArdle, Victor L. Katch. 1997.

Copyright ©1997

|